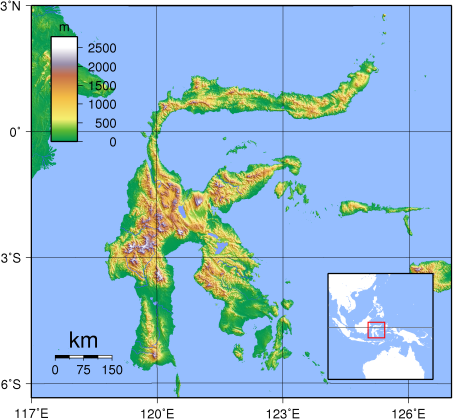

Two new Nepenthes species are described in the Philippine Journal of Science: Nepenthes malimumuensis and Nepenthes manobo (Lagunday, Acma, Cabana, Sabas, V.B. Amoroso). Both species are recorded from a single previously unexplored mountain in the Pantaron Range in Central Mindanao.

-

- The two new species bring the count of Nepenthes from the Pantaron range to seven species: endemics N. cornuta, N. malimumuensis, N. manobo, N. pantaronensis, and N. talaandig; plus N. surigaoensis and N. truncata

- N. malimumuensis is compared to N. sumagaya in the species description; N. sumagaya (first described as N. amabilis) had no obvious close relatives at the time of that species’ description and its lower pitchers could not be conclusively identified, so were not included in the description. N. malimumuensis lower pitchers are known and seem superficially similar to Insignes group members like N. insignis, but the lamina and floral morphology of N. malimumuensis and N. sumagaya definitely don’t support an inclusion in the Insignes group. The authors include N. malimumuensis into the N. villosa group based on morphological characteristics, although I think genetic studies may shed more light on the placement of these distinctive species.

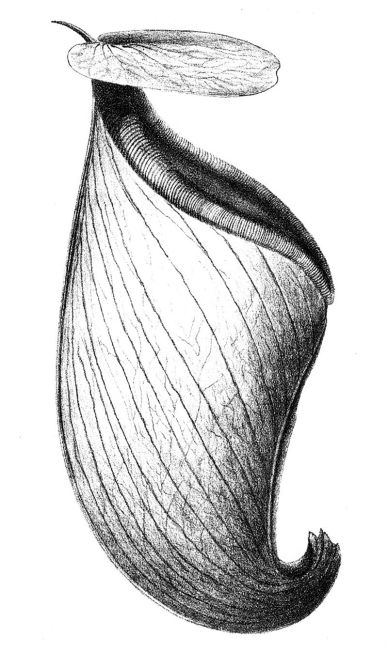

- N. manobo is compared to N. surigaoensis; these species are both members of the Insignes group although the bulbous bottom and cylindrical upper portion of N. manobo pitchers means this species cannot be easily confused with any other Insignes members.

- N. manobo was observed with “anomalous growth… in having two lids as shown in Figure 3B” (164). This is definitely NOT a stable nor defining characteristic of the species, but rather an interesting deformity noted by the authors on a single upper pitcher on a single vining plant.

- Both new species are only known from approximately 10 plants each and only observed on a single mountain; evidently both species are severely localized to a narrow altitudinal range (1000-1020 meters above sea level) and occur on ultramafic ridges. They are threatened by human encroachment, including illegal logging and quarrying.

Photos of N. malimumuensis and N. manobo can both be found on Co’s Digital Flora of the Philippines:

http://www.phytoimages.siu.edu/cgi-bin/dol/dol_terminal.pl?taxon_name=Nepenthes_malimumuensis&rank=binomial

http://www.phytoimages.siu.edu/cgi-bin/dol/dol_terminal.pl?taxon_name=Nepenthes_manobo&rank=binomial